On the evening of October 14, 1962, George and I were just kids on vacation, free from rules and bedtimes.

We laughed with Aunt Connie and Uncle Chuck while cousin Mike popped us bowls of popcorn, the buttery smell filling the kitchen. Later, we clanged away at the pinball machine in the garage, its flashing lights making us feel like the night could go on forever.

When we finally grew tired, we hugged and kissed Aunt Connie and Uncle Chuck goodnight, wrapped in their warmth, before curling up in our beds, safe and happy.

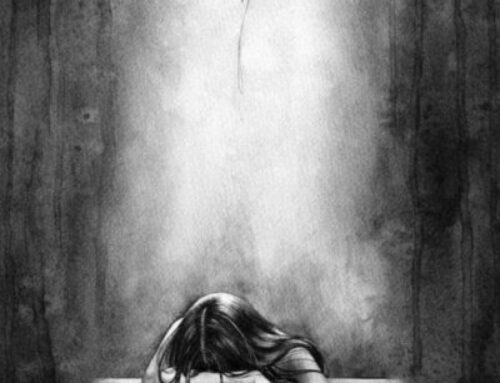

The house grew quiet. We drifted into sleep without a care in the world. But then, somewhere in the darkest hours, everything changed.

A sound split the silence — a scream.

Aunt Connie’s scream.

It was so sharp, so terrible, that it pulled me from the comfort of dreams and left me frozen with fear. ‘

Even now, I can still hear it, echoing inside me, though I didn’t fully understand what it meant. As George and I slept, unaware, our mother’s world was ending.

I didn’t know then — couldn’t have known — that she was gone at 10:40 p.m. that very night.

Gone before Aunt Connie’s scream ever reached my ears. Gone forever.

I have gathered every piece I could: the death certificate, the autopsy report, mortuary records, and the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department notes.

I even sought out neighbors who lived near us at the time.

From these fragments — the stories George and I were told as children, the revelations I uncovered in 1974, and the truths I’ve pieced together this past year — I have shaped the outline of what happened.

In 1974, I had to stop. What I uncovered then was already more than I could bear.

Yet one fact has never changed: my mother did not vanish, and she was not taken. She was at home. And she died there.

Still, the question of how has never been settled.

As a child, I could not comprehend it. As an adult, I still cannot.

Murder?

Suicide?

Neither word brings peace. Both leave only darkness. The records speak in fragments, never in full.

And so what remains is not truth, but echo — a scream that splits the night, a silence that stretches on, a shadow that has never lifted.

My heart knows my mother was terrified — gripped by a primal fear I would never wish upon another soul.

My heart knows she suffered.

In my dreams, I have seen her fighting for her life: clawing, scratching, her voice breaking into a deep, guttural cry — Aunt Connie’s scream echoing into the dark autumn sky.

And there was no one there to save her. No one should have to take their final breath in such terror, swallowed by pain and fear, their mind racing with desperate love for the children they must leave behind. I believe she thought of George and me in those last moments.

At the very least, I hold onto that — the hope that her final thoughts were of us.

It’s sick even to think it — sick to hope for something so twisted.

But I do.

I hope she thought of George and me as she was dying.

And then I picture it: her chest heaving, her body fighting, that last desperate gasp clawing at the air.

Terror flooding her, pain tearing through her, and somewhere inside it all — us.

Her children. The love she couldn’t carry forward.

What an incredibly fucked-up thing to hold on to — the idea that her last moments were split between agony and the thought of the two of us.

But that’s the truth I live with. A truth that never lets go.

Is this normal?

Ordinary?

I don’t know. What I do know is that when I let myself imagine my mother’s final moments, it rips me apart.

The pain is sharp, like a punch to the gut that never eases.

It sits heavy on my chest, crushing my heart, making it hard to breathe — like I can only steal the smallest sips of air while everything inside me splinters.

It’s brutal. It’s suffocating. It’s a million pounds pressing down, heavier than anyone could ever imagine.

October 15, 1964, began in horror, and from the very first breath of that day, I knew nothing would ever be the same. The memories are seared into me, as sharp and merciless now as they were then, refusing to fade no matter how many years have passed.

There was nothing ordinary about it, nothing that could ever be mistaken for routine — only chaos, shock, and devastation. It was, and always will be, the worst day of my life.

No one should ever have to lose a daughter, a mother, a sister, in such a way — stripped of dignity, discarded as though her life did not matter.

No one should have to carry the weight of such cruelty, such senseless disregard. And yet it happened.

It happened to us. It happened to her.

My mother — who deserved so much more, who deserved to be safe, to be cherished, to be alive — was taken in a way that can never be explained, never be justified.

And what remains is not peace, but echo — Aunt Connie’s scream, ripped from the depths of her, shattering the night sky, carrying farther and farther until it disappears into silence.

Except it never truly disappears. It stretches on, even now, as if the air itself still holds it, as if the night never let it go.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.