George learned resilience early.

Between the ages of six and eighteen, he lived through sustained psychological and physical harm. There were times I truly feared for our lives.

No one intervened—our alcoholic stepmother continued unchecked, and our father did not step in.

Against that backdrop, George’s later struggles with drinking, reckless choices, and incarceration are sadly understandable. The circumstances we came from were overwhelming.

Still, George refused to surrender optimism.

As children, we endured acts of cruelty that remain difficult to put into words. Once, our stepmother sprayed oven cleaner directly into George’s eye. I locked us in the laundry room and rinsed it as best I could with a wet cloth. He was left with a permanent scar beneath his left eye. On another occasion, she hurled a heavy wooden kitchen chair at him, breaking his arm.

At the hospital, we were forced to lie and say he had fallen, knowing that if we told the truth, food and water would be withheld as punishment.

One of the worst moments happened while our father stood by and watched.

George was stripped down to his underwear and forced to crawl in a circle—over hardware and rough carpet—210 times.

We were made to sit at the kitchen table and eat dinner as it happened. His knees were bloody. His breathing became frighteningly labored. I truly believed he might die. When I ran to get him a glass of water, I was slapped across the face and left with a bloody nose.

Our relationship with our stepmother was purely about survival.

Through it all, George would whisper to me, think ahead.

Believe this isn’t forever.

He made me promise never to give up—because giving up, he believed, would mean we wouldn’t survive.

I believe our childhood taught us that the human spirit has no true limits. Please understand that this series is not about child abuse.

For many years, George and I were reduced to the label of “those child-abuse kids.”

I acknowledge that I have spent more than 35 years working with at-risk youth, in part because of the compassion and support others extended to George and me later in life.

That generosity helped shape what became my life’s work.

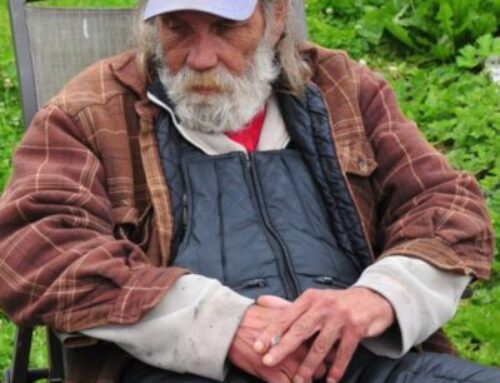

For much of his life, George lived one minute at a time, and I often wondered whether he would fully rise beyond what he had endured. I believe a turning point came when he moved to Port Alexander, Alaska.

There, at home in Port Alexander, he came to understand gratitude, personal responsibility, and an even more profound sense of resilience.

When we were children, Dotti would forbid us from speaking inside the house—sometimes for days at a time.

Absolute silence.

I developed a lisp that a schoolteacher eventually noticed, and George grew deeply uncomfortable speaking to anyone, even other children. At school, he was teased, as though silence meant something was wrong with him. George did find some freedom in sports. He played football and had natural coordination on the field, but a knee injury in high school brought that chapter to an early end.

At the time, California had no meaningful child-abuse protections or agencies to intervene.

George always wanted to be married and to have children of his own. That life never unfolded for him.

Near the end of his life, while he was in the hospital, he said to me:

“If you want to know the truth, sis, I still have a lot to learn. I still have things to figure out. I’ve just been doing the best I could. I don’t have all the answers. I’m just a regular person. My goal is to go home.”

This series reflects George’s wisdom as it truly was—simple, honest, and free of buzzwords.

His optimism was a quiet force that helped me endure life’s most challenging stretches. My appreciation for George as an individual only deepened, and in his final month, his gratitude and resilience were unmistakable.

The hospital’s willingness to let George and me connect freely by Zoom felt like a gift. In those moments, distance disappeared, and he spoke with unmistakable clarity.

In the years prior, speaking from his home in Port Alexander, we revisited the life only we truly understood—a history we seldom shared, because the odds we overcame often seem unbelievable to others.

George knew how much I loved writing; it was something he never cared for.

Before he died, he made me vow to keep writing—and that vow still carries me forward.

One of the last things he said to me was:

“I pray this time we have had together helps you, and please promise me that you will live a happy life. This is my wish for you, dear Doretta.”

The photo attached to this post was found in George’s wallet.

It was taken in June of 1964, when George was just eight years old, at our aunt’s home in Bellevue, Washington. One of our uncle’s boats clearly captured George’s affection.

Painted red and white, he always referred to it as a pretty boat. That picture reminds me that even in the hardest beginnings, there can still be beauty—and that sometimes, resilience starts with noticing a pretty boat and believing, quietly, that life can be more than what surrounds you.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.