The Stories We Believe

A well-told story invites belief. It doesn’t need to be true—it just needs to sound right. And we are often just as willing to believe the stories we tell ourselves. When we quietly ignore what should give us pause, it becomes remarkably easy to convince ourselves that a questionable choice is a good one.

We do it when we buy things beyond our means, settle into relationships that almost—but not quite—fit, or take financial risks that create long-term stress while promising short-term relief.

In those moments, we aren’t being honest with ourselves, which is why not every thought deserves our trust.

So what can we trust?

If we’re meant to take what others tell us with a grain of salt—whether it comes from books, podcasts, or the news—and we can’t fully trust our own thoughts either, what’s left?

Our feelings?

Probably not. Feelings matter, but they aren’t facts. They shift quickly and are often wrong. I’ve felt certain someone was annoyed with me, only to discover they weren’t. I’ve felt heavier than I was, only to see the scale tell a different story. I’ve felt incapable of doing something right up until the moment I did it. If thoughts deserve a grain of salt, feelings deserve an even bigger dose. When feelings of inadequacy surface, the kindest response is to pause and correct the story. The truth is, we are beautiful, blessed, capable, and far stronger than we realize.

Everything else is often just background noise—an unkind inner voice that thrives on criticism and doubt.

When thoughts are unreliable, opinions are biased, and feelings are unstable, lived experience becomes the only trustworthy reference point.

As the Chinese proverb says, “I hear, and I forget. I see, and I remember. But when I do, I understand.”

Firsthand experience needs no convincing.

The challenge lies in separating what actually happened from the thoughts, memories, and emotions we attach to it—because only the experience itself can be trusted.

Everything else is interpretation.

If we can remain unchanged by events that truly occurred, yet be deeply altered by events that existed only in our minds, then the greatest influence on our lives isn’t what happens to us—but how we perceive it.

This distinction becomes especially important when we confront painful truths.

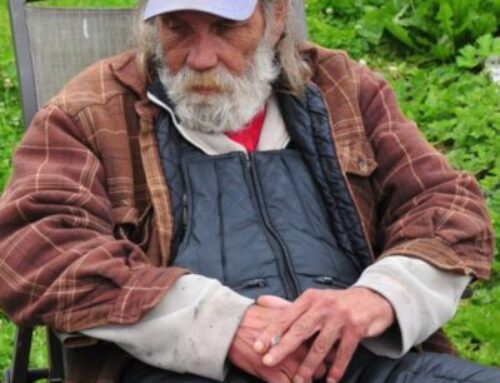

When abuse is passed down through generations, where does explanation end and accountability begin?

My stepmother harmed my brother and me, echoing patterns from her own past—yet the law named it for what it was: a crime.

She was charged twice. My father asked me to walk away from the charges, offering hope of a better life instead of justice.

Over time, I came to believe that within her own model of reality, she may not have thought she was doing anything wrong.

As Milton H. Erickson observed, people tend to make the best choices available to them given their model of the world.

Forgiving her was never about agreeing that what she did was right. It was about accepting that, to her, it made sense. That understanding allowed me to forgive her without abandoning my own truth.

Two truths existed at once—hers and mine.

Facts and truth are not the same thing.

I first learned that distinction from my high school science teacher. She explained that science is devoted to discovering facts, not defining truth.

Science seeks to understand how things occur, not why they exist.

Religion, by contrast, aims to answer the question of why and often elevates those answers to the level of unquestionable Truth—even when they conflict with observable facts.

Science, however, routinely revises or overturns earlier conclusions as new evidence emerges, even when doing so requires admitting previous interpretations were incomplete. That flexibility exists because science has no emotional attachment to being right—only to being accurate.

While individuals within religious traditions may evolve in their understanding, organized religion itself tends to preserve established doctrine, in part because revising one belief can introduce uncertainty across the entire system.

Which brings us back to ourselves.

It’s essential to regularly revisit our beliefs and values—and to let them go when they no longer fit.

What once felt true may not be true today. Some beliefs outlive their usefulness, and clinging to them is like wearing an old pair of glasses that no longer allows us to see clearly. Growth doesn’t come from defending outdated stories. It comes from updating the lenses through which we see.

And sometimes, the bravest thing we can do is admit that what once made sense no longer does—and choose clarity instead.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.