The Truth That Refused to Stay Buried

A personal investigation into a mother’s death—and the unanswered questions that remain

Some truths arrive quietly, and others that fracture a life. This story is about the latter. What follows is not speculation for its own sake, nor a sensational retelling.

It is the lived experience of a daughter who was told one story for twelve years—and then discovered another.

It is an account shaped by memory, documentation, absence, and the ache of what cannot be reconciled.

The Continued Story of A Girl Left Behind

Had my mother died in an accident, I believe I would have eventually been able to understand and integrate her loss.

From the age of nine until I was twenty-one, I was told she had died of cancer, an illness. Accidents occur. Illnesses claim lives. Death is an undeniable part of the human experience.

What altered everything was discovering, at twenty-one, through her death certificate, that her death was recorded as a suicide.

She was believed to have consciously chosen to end her life as a young mother of two children.

That explanation never made sense to me—then or now—and I continue to search for the truth of what really happened. The facts surrounding my mother’s death suggest a level of violence that is deeply disturbing.

The images of what the scene may have been like haunt me, creating visions that leave me struggling to breathe as I imagine her fear. I ask myself whether she was alone. I find it difficult to share the details I have uncovered over years of investigation, knowing how painful it was for me to read them. This is not what I want you to remember about my mother. But it is part of her story, and the truth of what I have discovered cannot remain unspoken.

These are the facts as I understand them today. I have no memory of my mother being ill.

She was actively involved in my schooling and in George’s, participated in my BlueBirds, and kept an open-door home for the children in our neighborhood. She worked, cared for the many animals we had, and was engaged in community activities that were noted in the local newspaper. She had close girlfriends who visited our home, went out to dinner with friends, and hosted Thanksgiving and Christmas gatherings where our entire family came together.

Then, on October 14, 1962, at 10:40 p.m., her life ended.

From that moment on, everything disappeared. I never saw my mother again.

I never returned to our home, to my room, never saw my goldfish, my books, my clothes, my favorite red shoes, never slept in my own little bed again, never returned to our animals, to my friends, my teachers, or any part of the life we had in San Bernardino. According to her death certificate, my mother died in our home that evening. Of the neighbors, only one has ever offered any account of seeing her—or anyone else—on that day.

To my knowledge, my mother did not leave the house, and there is no official record indicating that anyone else was present. Beyond what is handwritten on the death certificate, there are no detailed accounts of how her life ended. With so little information, I am left to assume that the last time my mother said goodbye to George and me was during our final conversation at Aunt Connie’s. And that sometime after, everything went terribly wrong.

Did someone else enter the house that day?

Was another vehicle ever seen in our driveway?

Was it someone she knew?

Did things go sideways?

I do not want to imagine the scenario that has emerged from my investigation, yet I cannot dismiss it as a possibility. With the perspective of adulthood, I understand that people—even my mother—can find themselves in situations they are not prepared to navigate.

None of us is perfect; all of us are capable of missteps. As my investigation deepens, the possible explanations continue to accumulate, yet clarity does not. There are no clear answers, and there may never be.

What I know is this: my mother’s death certificate lists the informant as my grandfather, George E. Bell, who resided in San Leandro—more than six hours away.

The physician is typed as R. E. Williams.

The coroner’s name, however, is handwritten and belongs to a different individual whose name does not appear anywhere else in the available records.

Despite these inconsistencies, the death certificate was signed, and the cause of death was determined at that moment—before an autopsy was performed and before the documentation of her autopsy.

The document then indicates that my mother’s body was transported the following day to the Clarence M. Cooper Mortuary in Oakland, another six hours away, again before the documentation of her autopsy.

The embalmer’s name is handwritten and accompanied by a license number, though there is no single, comprehensive national online database to verify these historical professions. The funeral director is listed as Mark B. Shaw at Kremer Chapel.

Mark B. Shaw Funeral Directors is a mortuary and business entity located in San Bernardino, California.

George W. Smith, M.D., also signed the death certificate.

The cause of death is handwritten as “Gunshot wound of heart,” then typed as “Sucicide,” with a correction made to the misspelling.

It is further typed as “Self-inflicted – Gun Shot Wound into chest to heart.”

The sequence of events does not align with what would be expected. Logic leaves me with the sense that something in this progression is not quite right. For decades, the possibility of what may have been unfolding—across multiple individuals—has stayed with me.

The inhumanity implied is difficult to comprehend, and the pain involved is beyond what I can easily imagine.

I am left to wonder whether others were involved in concealing the truth.

In the 1960s, deaths ruled as suicide were not examined through the collection of physical evidence.

The images my mind has carried over the years remain deeply embedded, refusing to fade.

The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department reports that no crime scene photographs exist, no notes were recovered, and there is no record of the firearm involved.

Firearms were not part of our household, and my mother was not someone who used them. My mind instinctively recoils at the thought of that night.

Because the family was required—at my father’s insistence—to uphold the false story George and I were told, that she died of cancer, many of the events surrounding her death remain unknown to me.

I do not know who contacted the police, who may have heard a gunshot, or whether anyone else was seen at the house, aside from one individual who has since come forward.

When my grandfather was notified, did he then drive to San Bernardino to report what had occurred?

And when she was found, had she already been dead for hours?

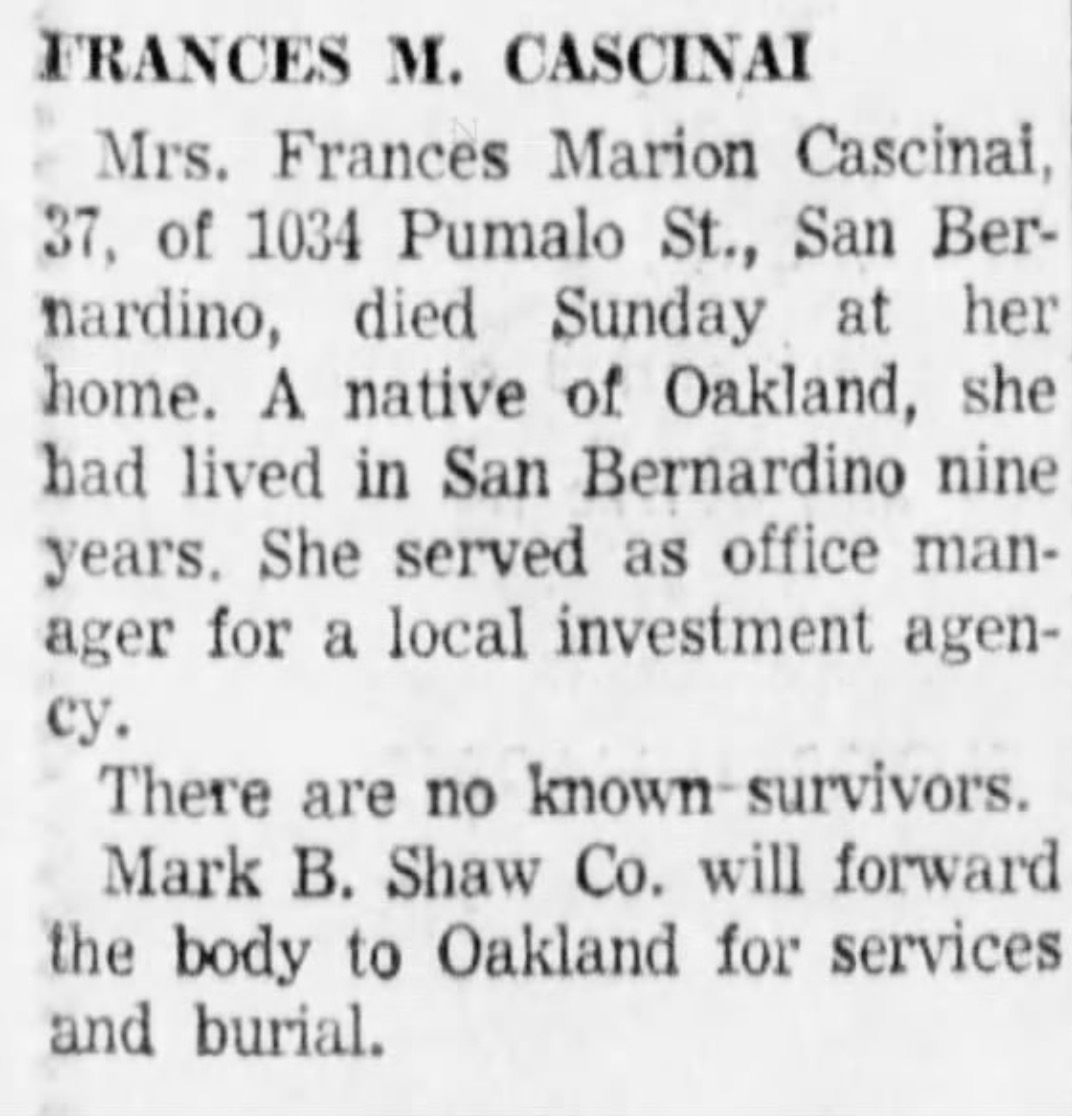

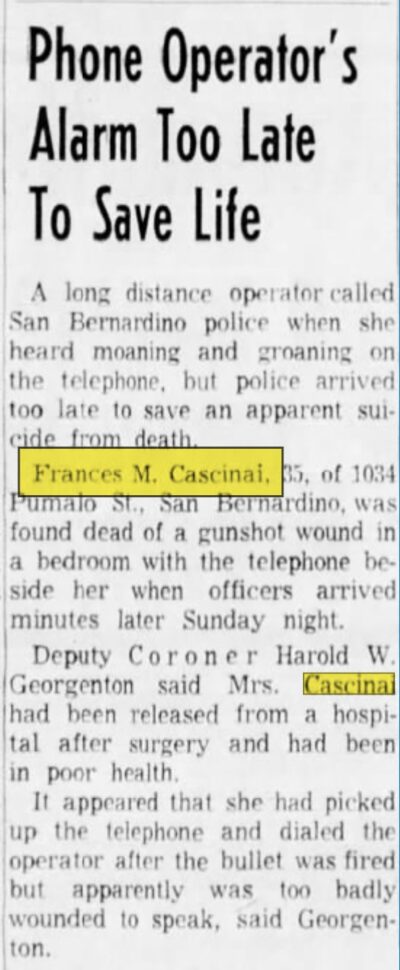

Three newspaper articles appeared in the local paper on October 16, 1962.

Two of them stated that there were no known survivors, effectively erasing George and me as her surviving children. A third article described a phone operator receiving a call; however, this account has never been verified and does not align with information obtained from other sources.

That article introduces multiple contradictions.

It claims that a long-distance operator received a call and that “moaning and groaning” was heard, yet the death certificate states that death was immediate.

The article also reports that my mother was found dead from a gunshot wound, then goes on to assert that she had recently been released from the hospital following surgery and had been in poor health. No mention of suicide appears until a later article is published. None of this information has ever been verified. No hospital records from that time exist, and neither her sisters nor her parents ever confirmed any hospitalization or decline in her health.

The source of these claims remains unknown; no individual has been identified or corroborated.

The suggestion that my mother picked up the phone and dialed an operator after the gunshot directly contradicts the coroner’s finding of immediate death.

Additionally, Deputy Coroner Harold W. Georgenton is not listed on the death certificate or on the autopsy report. It remains unclear who provided him with the information.

Why This Story Matters

This is not only a personal reckoning—it is a reflection of how stories are shaped by authority, silence, and time. It raises questions about recordkeeping, about whose voices are preserved, and about the cost of asking children to carry lies they did not choose.

Truth, even when incomplete, deserves air.

Reflection: What Remains

I do not write this to accuse, nor to claim certainty where none exists. I write because silence has weight, and unanswered questions do not disappear simply because decades have passed.

They live in the body. They surface in quiet moments. They ask to be acknowledged. My mother was not an abstract cause of death on a form. She was a woman with a life in motion, a mother with children she loved, a presence rooted in community, friendship, and care. Whatever happened that night does not erase who she was before it. I may never know the full truth. Records are missing. Witnesses are gone. Time has taken what it takes. But uncertainty does not invalidate inquiry, and absence of proof is not proof of absence.

What I know—what I hold onto—is that truth matters, even when it arrives incomplete.

Especially then.

This reflection is not an ending to this yet-to-be-written story of The Girl Left Behind.

It is an act of bearing witness to naming what was hidden. Of refusing to let a life be reduced to a single word written in haste, misspelled, and left unquestioned. My mother’s story deserves care. So does the child who lived inside a false narrative for twelve years. So does the adult who continues to ask, not out of suspicion alone, but out of love. Some truths do not arrive as answers.

They arrive as commitments: to remember, to question, and to tell the story as honestly as possible.

This is mine.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.